What’s the goal, anyway?

When we oppose injustice, what are we hoping for?

I was an hour into an interview with a woman I’ll call Sarah when she suddenly burst out, “What is the goal? I have no idea!”

I had just asked Sarah a question I included in every research interview–“When you hope for racial justice, what does that mean? What do you hope for?”

It turns out a lot of people haven’t thought much about that. “There’s something that just feels unsettling about training folks to be in a stance of opposition toward something without being very clear about what we are a proponent for,” psychologist Dr. Krystal Hays said in a recent interview about her co-authored book, Healing Conversations on Race. “That’s the piece that feels like something is missing.” As a clinical psychologist, Hays said she would never ask someone to be “anti-drug-user.” You can’t just name what you’re avoiding. You have to know what you desire. What vision draws you forward?

I was surprised by how many people struggled to name their hopes. Somewhere in the language of “anti-racism,” too many conversations seem to have lost focus on what we’re aiming for.

But people did eventually answer, and I’d like to hear your thoughts on a metaphor I’ve found helpful for summarizing their answers.

The goal is to become menders of the social fabric together.

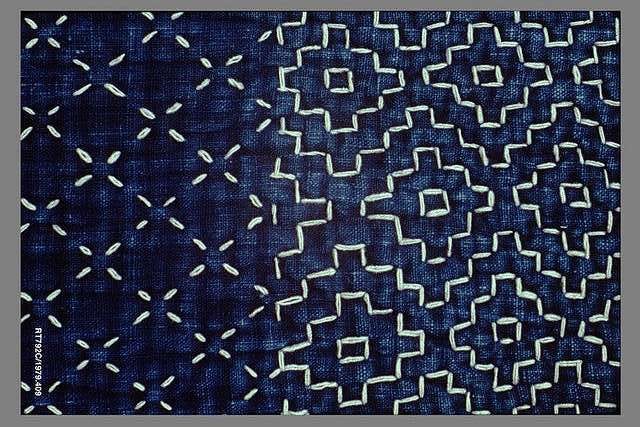

My friend told me recently about an old Japanese art form called boro. Working-class people several centuries ago would stitch together patches of simple, hand-woven fabrics in patterns that were both ruggedly practical and tenderly beautiful. Historically, people made boro of plain cotton threads and fabrics dyed with the cheapest blue.

Instead of hiding the repairs, boro was often sewn using sashiko, a technique of tiny stitch patterns that decorate even as they reinforce. Instead of chucking out a clothing article, sashiko makes the repair itself into a thing of joy. The mending restores functionality and also traces a story of meaning and love across that fabric.

Becoming a restorer of justice is a lot like boro and sashiko. You take something torn and start a pattern of stitching. The fabric you’re repairing isn’t just a shirt or a sleeping mat, it’s the very fabric of society. You create through what you have at hand. Your relationships become the stitching that weaves us together.

Unlike some problems (say, ingrown toenails and broken door hinges), racism is a social problem. When that social fabric tears, society can’t function as it should. A torn society can’t distribute resources, ideas, and culture in ways that produce flourishing, meaning, and love.

And so the goal in ending racism is to become menders of the social fabric. Like the clothes on your back, social fabric keeps on getting snagged and worn out. It’s no use aiming to have it all mended once and for all. Instead, we aim to keep on weaving ourselves together, fixing the broken systems, and finding joy through turning fissures into functional art.

Sarah eventually settled on her answer. “Mutuality. Maybe that’s the goal.” We mend the social fabric by mutually passing threads of trust, resources, and grace back and forth, giving attention to the snags instead of hiding them away. We develop habits of restoration and celebration. We become better stories.

What do you think? Do you have metaphors or words that help keep your eyes on the goals of justice? I’d love to hear your ideas.