On a lot of holidays, the emotions we’re supposed to feel seem pretty clear.

Easter? Happy.

Independence Day? Happy.

Thanksgiving? Grateful.

Memorial Day? Grateful and maybe a little sad.

Christmas? Happy and grateful (and maybe a little greedy).

But Juneteenth? Less clear. Happy? Sorrowful? Hopeful? Proud? Reverent? It’s the kind of holiday that calls into question not just our emotions on this day, but all the emotions we’ve been told to feel on most other holidays, too.

When President Biden signed the document making Juneteenth a national holiday, he said this:

"On Juneteenth, we recommit ourselves to the work of equity, equality, and justice. And we celebrate the centuries of struggle, courage, and hope that have brought us to this time of progress and possibility. That work has been led throughout our history by abolitionists and educators, civil rights advocates and lawyers, courageous activists and trade unionists, public officials, and everyday Americans who have helped make real the ideals of our founding documents for all."

On the surface, he’s saying to feel celebratory. Juneteenth has also been called Jubilee Day, Emancipation Day, and Freedom Day, and it marks the happy occasion of the freeing of the last African American slaves on June 19, 1865. So indeed, happiness is appropriate.

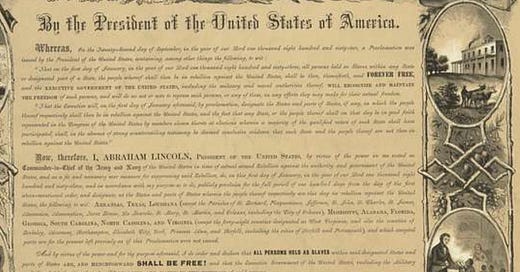

But how do you reconcile that happiness with the rest of the story? With the struggle, the enslavement, the two long years that passed between the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation and freeing of the last enslaved individuals? And is happiness appropriate for the continued racism and struggle through the 159 years since? Certainly, this is also a day of lament.

I wonder if part of the tension many non-Black Americans feel in figuring out what to do around Juneteenth is a discomfort with holding conflicting realities in tension.

But learning to hold opposing ideas in tension can also inform our observances of other national holidays. For all the times I sang the Star-Spangled Banner and oohed over fireworks displays on Independence Days growing up, I never considered how that line “bombs bursting in air” also points to the many bombs that did not burst in air, but on homes and human beings. For me it took attending a Fourth of July fireworks display put on my American diplomats in Uganda to realize what a strange celebratory practice this is.

The holidays we grow up learning to see as victories are rarely victories for everyone. Thanksgiving is a day of gratitude for the survival of Europeans who settled in new homes and the peaceful relationships they had with many indigenous people, but it’s also a day of lament for the vast destruction of indigenous American ways of life brought about by European settlers. Even Christmas and Easter, as much as they celebrate God’s love and power, also point Christians’ attention forward and backward to the brutal death of Christ Jesus.

But we can do this. We can hold conflicting emotions in tension and be better people because of it. We can acknowledge that history is not a story of good folks versus bad folks. It’s a story of many complicated individuals, events, and systems. I’ve appreciated Brené Brown’s work on this topic, and her interview with President Barack Obama is a great way to delve into how to lean into uncertainty and hold the tension of opposites.

It's a tension I feel as I learn how people hope for racial justice even amidst reasons for despair. It’s a tension I feel as I deal with everyday practical questions, like whether playing jazz music as a white musician is an act of cultural appropriation. It’s a tension I feel living and working in predominantly white spaces and benefitting from the history of racism in this nation. But the only way to escape that tension altogether is ignorance, and I choose the path of acknowledgement instead.

Juneteenth marks a historical storyline, and like all history, it’s complicated. It can evoke emotions from joy to sorrow. There’s not one single right way to celebrate Juneteenth. You might attend a parade or festival, incorporate it into a church service, take time to learn about African American history, support a Black-owned businesses, or check out these other ideas. If you’re white, it’s not about ce

lebrating you, but that doesn’t mean you should ignore the holiday. It’s about all of us honoring a story of harm, healing, and hope.

Let’s keep our holidays complicated. And celebrate anyway.